With brilliant red-orange flowers appearing intermittently throughout the warmer half of the year, Haemodorum coccineum (Haemodoraceae) is a fitting selection to represent multiple months. (Our web editor was too busy to do a new one each month, sorry!)

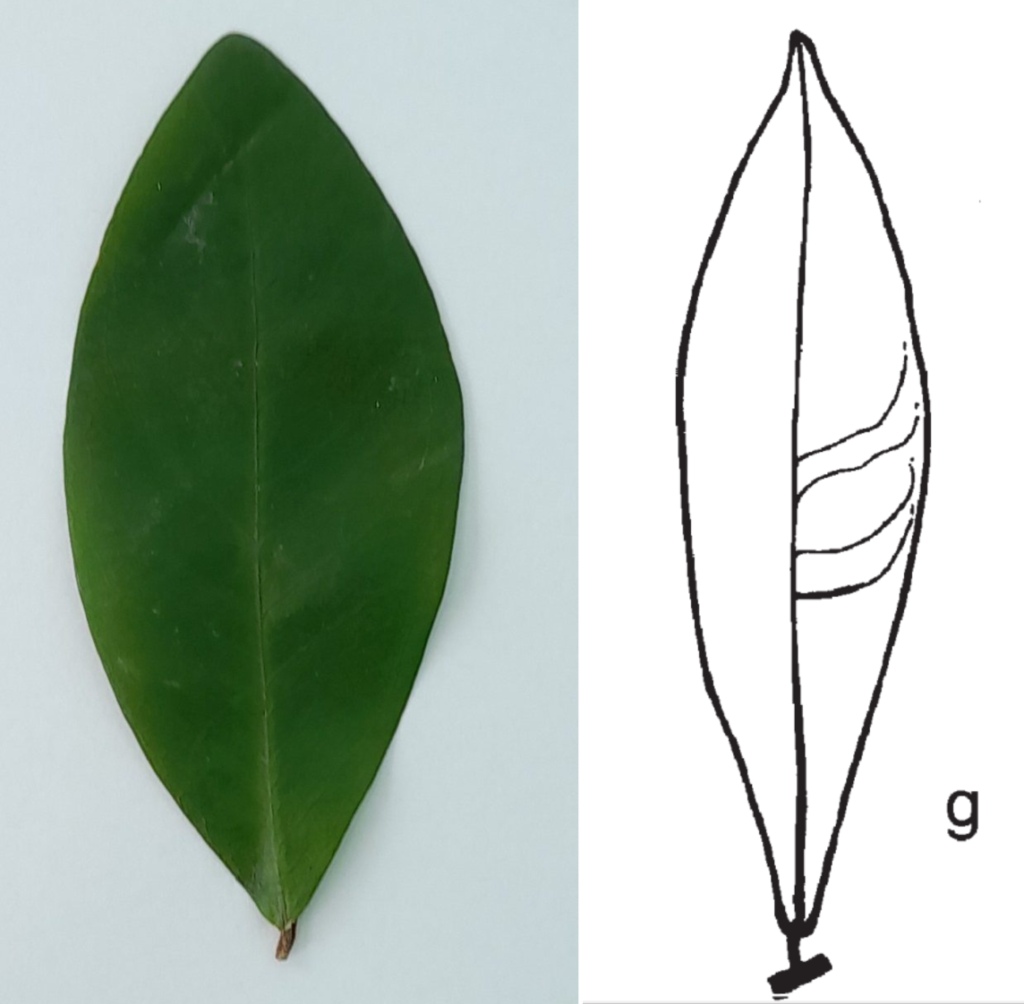

Commonly called Bloodroot, due to the colour of its underground parts, this attractive local plant grows a clump of strap-like leaves, sometimes mistaken for a grass or Lomandra species until its distinctive flowers appear.

The leaves often die back during the dry season and then regrow from the underground rhizome at the start of the next wet season.

Haemodorum coccineum can be easily grown in Townsville gardens, preferring moist but well-drained soil and partial or full sun. It makes a fine show if planted in dense groups.

Indigenous Australians used various Haemadorum species for traditional medicinal purposes and extracted a high-quality red dye from the flowers and roots.

In 2006 Haemodorum coccineum was favourably assessed in a government-funded study into its potential as a new cut-flower species, but it seems there has been no substantial commercial production as yet.